In the 2011 documentary Jiro Dreams of Sushi, then 85 year-old sushi master Jiro Ono says this about craft:

Once you decide on your occupation… you must immerse yourself in your work. You have to fall in love with your work. Never complain about your job. You must dedicate your life to mastering your skill. That’s the secret of success and is the key to being regarded honorably.

Craft is typically thought of as the formal aspects of any field such as design, woodworking, writing, or cooking. In design, we think about composition, spacing, and typography—being pixel-perfect. But one’s craft is much more than that. Ono’s sushi craft is not solely about slicing fish and pressing it against a bit of rice. It is also about picking the right fish, toasting the nori just so, cooking the rice perfectly, and running a restaurant. It’s the whole thing.

Therefore, mastering design—or any occupation—takes time, experience, or reps as the kids say. So it’s to my dismay that Suff Syed’s essay “Why I’m Giving Up My Design Title — And What That Says About the Future of Design” got so much play in recent weeks. Syed is Head of Product Design at Microsoft—er, was. I guess his title is now Member of the Technical Staff. In a perfectly well-argued and well-written essay, he concludes:

That’s why I’m switching careers. From Head of Product Design to Member of Technical Staff.

This isn’t a farewell to experience, clarity, or elegance. It’s a return to first principles. I want to get closer to the metal—to shape the primitives, models, and agents that will define how tomorrow’s software is built.

We need more people at the intersection. Builders who understand agentic flows and elevated experiences. Designers who can reason about trust boundaries and token windows. Researchers who can make complex systems usable—without dumbing them down to a chat interface.

In the 2,800 words preceding the above quote, Syed lays out a five-point argument: the paradigm for software is changing to agentic AI, design doesn’t drive innovation, fewer design leaders will be needed in the future, the commoditization of design, and the pay gap. The tl;dr being that design as a profession is dead and building with AI is where it’s at.

With respect to Mr. Syed, I call bullshit.

Let’s discuss each of his arguments.

The Paradigm Argument

Suff Syed:

The entire traditional role of product designers, creating static UI in Silicon Valley offices that work for billions of users, is becoming increasingly irrelevant; when the Agent can simply generate the UI it needs for every single user.

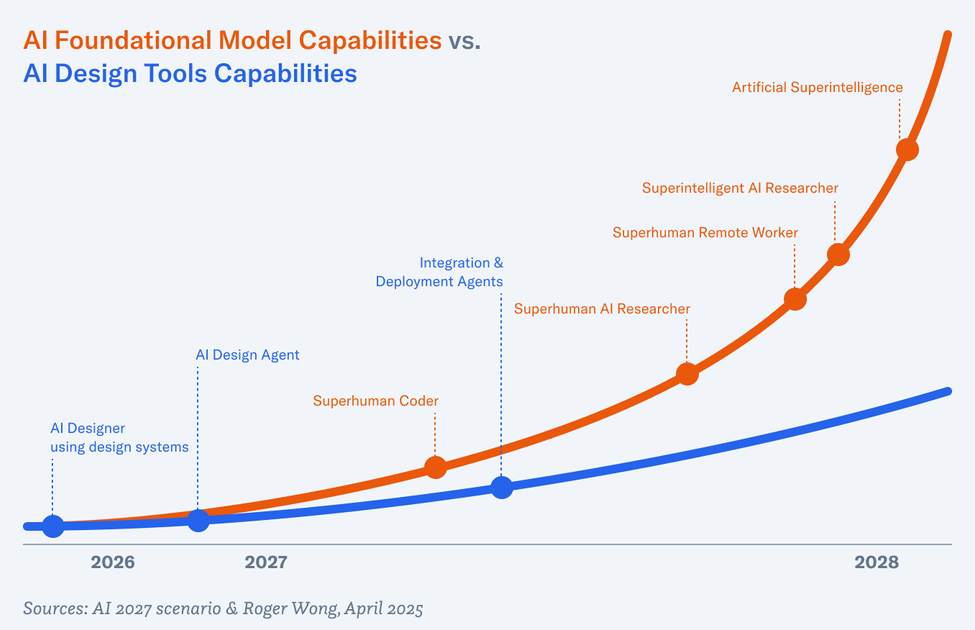

That’s a very narrow view of what user experience designers do. In this diagram by Dan Saffer from 2008, UX encircles a large swath of disciplines. It’s a little older so it doesn’t cover newer disciplines like service design or AI design.

Originally made by envis pricisely GmBH - www.envis-precisely.com, based on “The Disciplines of UX” by Dan Saffer (2008). (PDF)

I went to design school a long time ago, graduating 1995. But even back then, in Graphic Design 2 class, graphic design wasn’t just print design. Our final project for that semester was to design an exhibit, something that humans could walk through. I’ve long lost the physical model, but my solution was inspired by the Golden Gate Bridge and how I had this impression of the main cables as welcome arms as you drove across the bridge. My exhibit was a 20-foot tall open structure made of copper beams and a glass roof. Etched onto the roof was a poem—by whom I can’t recall—that would cast the shadows of its letters onto the ground, creating an experience for anyone walking through the structure.

Similarly, thoughtful product designers consider the full experience, not just what’s rendered on the screen. How is onboarding? What’s their interaction with customer service? And with techniques like contextual inquiry, we care about the environments users are in. Understanding that nurses in a hospital are in a very busy setting and share computers are important insights that can’t be gleaned from desk research or general knowledge. Designers are students of life and observers of human behavior.

Syed again:

Agents offer a radical alternative by placing control directly into users’ hands. Instead of navigating through endless interfaces, finding a good Airbnb could be as simple as having a conversation with an AI agent. The UI could be generated on the fly, tailored specifically to your preferences; an N:1 model. No more clicking around, no endless tabs, no frustration.

I don’t know. I have my doubts that this is actually going to be the future. While I agree that agentic workflows will be game-changing, I disagree that the chat UI is the only one for all use cases or even most scenarios. I’ve previously discussed the disadvantages of prompting-only workflows and how professionals need more control.

I also disagree that users will want UIs generated on the fly. Think about the avalanche of support calls and how insane those will be if every user’s interface is different!

In my experience, users—including myself—like to spend the time to set up their software for efficiency. For example, in a dual-monitor setup, I used to expose all of Photoshop’s palettes and put them in the smaller display, and the main canvas on the larger one. Every time I got a new computer or new monitor, I would import that workspace so I could work efficiently.

Habit and muscle memory are underrated. Once a user has invested the time to arrange panels, tools, and shortcuts the way they like, changing it frequently adds friction. For productivity and work software, consistency often outweighs optimization. Even if a specialized AI-made-for-you workspace could be more “optimal” for a task, switching disrupts the user’s mental model and motor memory.

I want to provide one more example because it’s in the news: consider the backlash that OpenAI has faced in the past week with their rollout of GPT-5. OpenAI assumed people would simply welcome “the next model up,” but what they underestimated was the depth of attachment to existing workflows, and in some cases, to the personas of the models themselves. As Casey Newton put it, “it feels different and stronger than the kinds of attachment people have had to previous kinds of technology.” It’s evidence of how much emotional and cognitive investment users pour into the tools they depend on. You can’t just rip that foundation away without warning.

Which brings us back to the heart of design: respect for the user. Not just their immediate preferences, but the habits, muscle memory, and yes, relationships that accumulate over time. Agents may generate UIs on the fly, but if they ignore the human need for continuity and control, they’ll stumble into the same backlash OpenAI faced.

The Innovation Argument

Syed’s second argument is that design supports innovation rather than drive it. I half agree with this. If we’re talking about patents or inventions, sure. Technology will always win the day. But design can certainly drive innovation.

He cites Airbnb, Figma, Notion, and Linear as being “incredible companies with design founders,” but only Airbnb is a Fortune 500 company.

While not having been founded by designers, I don’t think anyone would argue that Apple, Nike, Tesla, and Disney are not design-led and aren’t innovative. All are in the Fortune 500. Disney treats experience design, which includes its parks, media, and consumer products, as a core capability. Imagineering is a literal design R&D division that shapes the company’s most profitable experiences. Look up Lanny Smoot.

Early prototypes of the iPhone featuring the first multitouch screens were actually tablet-sized. But Apple’s industrial design team led by Jony Ive, along with the hardware engineering team got the form factor to fit nicely in one hand. And it was Bas Ording, the UI designer behind Mac OS X’s Aqua design language that prototyped inertial effects. Farhad Manjoo, writing in Slate in 2012:

Jonathan Ive, Apple’s chief designer, had been investigating a technology that he thought could do wonderful things someday—a touch display that could understand taps from multiple fingers at once. (Note that Apple did not invent multitouch interfaces; it was one of several companies investigating the technology at the time.) According to Isaacson’s biography, the company’s initial plan was to the use the new touch system to build a tablet computer. Apple’s tablet project began in 2003—seven years before the iPad went on sale—but as it progressed, it dawned on executives that multitouch might work on phones. At one meeting in 2004, Jobs and his team looked a prototype tablet that displayed a list of contacts. “You could tap on the contact and it would slide over and show you the information,” Forstall testified. “It was just amazing.”

Jobs himself was particularly taken by two features that Bas Ording, a talented user-interface designer, had built into the tablet prototype. One was “inertial scrolling”—when you flick at a list of items on the screen, the list moves as a function of how fast you swipe, and then it comes to rest slowly, as if being affected by real-world inertia. Another was the “rubber-band effect,” which causes a list to bounce against the edge of the screen when there were no more items to display. When Jobs saw the prototype, he thought, “My god, we can build a phone out of this,” he told the D Conference in 2010.

The Leadership Argument

Suff Syed’s third argument is about what it means to be a design leader. He says, “scaling your impact as a designer meant scaling the surfaces you influence.” As you rose up through the ranks, “your craft was increasingly displaced by coordination. You became a negotiator, a timeline manager, a translator of ambition through Product and Engineering partnerships.”

Instead, he argues, because AI can build with fewer people—well, you only need one person: “You need two people: one who understands systems and one who understands the user. Better if they’re the same person.”

That doesn’t scale. Don’t tell me that Microsoft, a company with $281 billion in revenue and 228,000 employees—will shrink like a stellar collapse into a single person with an army of AIs. That’s magical thinking.

Leaders are still needed. Influence and coordination are still needed. Humans will still be needed.

He ends this argument with:

This new world despises a calendar full of reviews, design crits, review meetings, and 1:1s. It emphasizes a repo with commits that matter. And promises the joy of shipping to return to your work. That joy unmediated by PowerPoint, politics, or process. That’s not a demotion. That’s liberation.

So he wants us all to sit in our home offices and not collaborate with others? Innovation no longer comes from lone geniuses. They’re born from bouncing ideas off of your coworkers and everyone building on each other’s ideas.

Friction in the process can actually make things better. Pixar famously has a council known as the Braintrust—a small, rotating group of the studio’s best storytellers who meet regularly to tear down and rebuild works-in-progress. The rules are simple: no mandatory fixes, no sugarcoating, and no egos. The point is to push the director to see the story’s problems more clearly—and to own the solution. One of the most famous saves came with Toy Story 2. Originally destined for direct-to-video release, early cuts were so flat that the Braintrust urged the team to start from scratch. Nine frantic months later, the film emerged as one of Pixar’s most beloved works, proof that constructive creative friction can turn a near-disaster into a classic.

The Distribution Argument

Design taste has been democratized and is table stakes, says Syed in his next argument.

There was a time when every new Y Combinator startup looked like someone tortured an intern into generating a logo using Clipart. Today, thanks to a generation of exposure to good design—and better tools—most founders have internalized the basics of aesthetic judgment. First impressions matter, and now, they’re trivial to get right.

And that templates, libraries, and frameworks make it super easy and quick to spin up something tasteful in minutes:

Component libraries like Tailwind, shadcn/ui, and Radix have collapsed the design stack. What once required a full design team handcrafting a system in Figma, exporting specs to Storybook, and obsessively QA-ing the front-end… now takes a few lines of code. Spin up a repo. Drop in some components. Tweak the palette. Ship something that looks eerily close to Linear or Notion in a weekend.

I’m starting to think that Suff Syed believes that designers are just painters or something. Wow. This whole argument is reductive, flattening our role to be only about aesthetics. See above for how much design actually entails.

The Wealth Argument

“Nobody is paying Designers $10M, let alone $100M anytime soon.” Ah, I think this is him saying the quiet part out loud. Mr. Syed is dropping his design title and becoming a “member of the technical staff” because he’s chasing the money.

He’s right. No one is going to pay a designer $100 million total comp package. Unless you’re Jony Ive and part of io, which OpenAI acquired for $6.5 billion back in May. Which is a rare and likely once-ever occurrence.

In a recent episode of Hard Fork, The New Times tech columnist Kevin Roose said:

The scale of money and investment going into these AI systems is unlike anything we’ve ever seen before in the tech industry. …I heard a rumor there was a big company that wasted a billion dollars or more on a failed training run. And then you start to think, oh, I understand why, to a company like Meta, the right AI talent is worth a hundred million dollars, because that level of expertise doesn’t exist that widely outside of this very small group of people. And if this person does their job well, they can save your company something more like a billion dollars. And maybe that means that you should pay them a hundred million dollars.

“Very small group of people” is likely just a couple dozen people in the world who have this expertise and worth tens of millions of dollars.

Syed again:

People are getting generationally wealthy inventing new agentic abstractions, compressing inference cycles, and scaling frontier models safely. That’s where the gravity is. That’s where anybody should aspire to be. With AI enabling and augmenting you as an individual, there’s a far more compelling reason to chase this frontier. No reason not to.

People also get generationally wealthy by hitting the startup lottery. But it’s a hard road and there’s a lot of luck involved.

The current AI frenzy feels a lot like 1849 in California. Back then, roughly 300,000 people flooded the Sierra Nevada mountains hoping to strike gold, but the math was brutal: maybe 10% made any profit at all, the top 4% earned enough to brag a little, and only about 1% became truly rich. The rest? They left with sore backs, empty pockets, and I guess some good stories.

Back to Reality

AI is already changing the software industry. As designers and builders of software, we are going to be using AI as material. This is as obvious as when the App Store on iPhone debuted and everyone needed to build apps.

Suff Syed wrote his piece as part personal journey and decision-making and part rallying cry to other designers. He is essentially switching careers and says that it won’t be easy.

This transition isn’t about abandoning one identity for another. It’s about evolving—unlearning what no longer serves us and embracing the disciplines that will shape the future. There’s a new skill tree ahead: model internals, agent architectures, memory hierarchies, prompt flows, evaluation loops, and infrastructure that determines how products think, behave, and scale.

Best of luck to Suff Syed on his journey. I hope he strikes AI gold.

As for me, I aim to continue on my journey of being a shokunin, or craftsman, like Jiro Ono. For over 30 years—if you count my amateur days in front of the Mac in middle school—I’ve been designing. Not just pushing pixels in Photoshop or Figma, but doing the work of understanding audiences and users, solving business problems, inventing new interaction patterns, and advocating for usability. All in the service of the user, and all while honing my craft.

That craft isn’t tied to a technology stack or a job title. It’s a discipline, a mindset, and a lifetime’s work. Being a designer is my life.

So no, I’m not giving up my design title. It’s not a relic—it’s a commitment. And in a world chasing the next gold rush, I’d rather keep making work worth coming back to, knowing that in the end, gold fades but mastery endures. Besides, if I ever do get rich, it’ll be because I designed something great, not because I happened to be standing near a gold mine.