Product Design Is Changing

I made my first website in Macromedia Dreamweaver in 1999. Its claim to fame was an environment with code on one side and a rudimentary WYSIWYG editor on the other. My site was a simple portfolio site, with a couple of animated GIFs thrown in for some interest. Over the years, I used other tools to create for the web, but usually, I left the coding to the experts. I’d design in Photoshop, Illustrator, Sketch, or Figma and then hand off to a developer. Until recently, with rebuilding this site a couple of times and working on a Severance fan project.

A couple weeks ago, as an experiment, I pointed Claude Code at our BuildOps design system repo and asked it to generate a screen using our components. It worked after about three prompts. Not one-shotted, but close. I sat there looking at a functioning UI—built from our actual components—and realized I’d just skipped the entire part of my job that I’ve spent many years doing: drawing pictures of apps and websites in a design tool, then handing them to someone else to build.

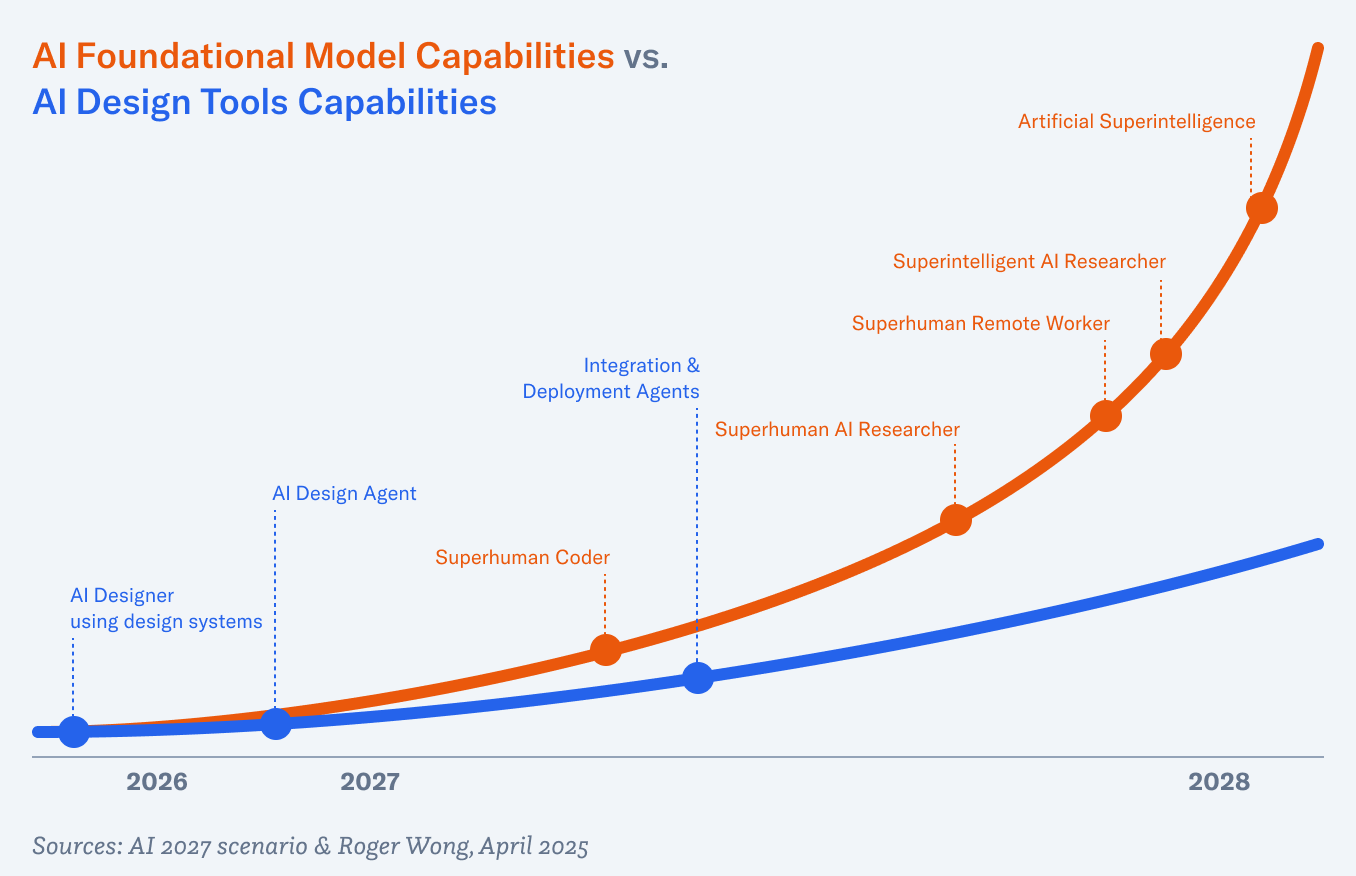

That moment crystallized something I’d been circling all last year. I wrote last spring about how execution skills were being commoditized and the designer’s value was shifting toward taste and strategic direction. A month later I mapped out a timeline for how design systems would become the infrastructure that AI tools generate against—prompt, generate, deploy. That was ten months ago, and most of it is already happening. Product design is changing. Not in the way most people are talking about it, but in a way that’s more fundamental and more interesting.