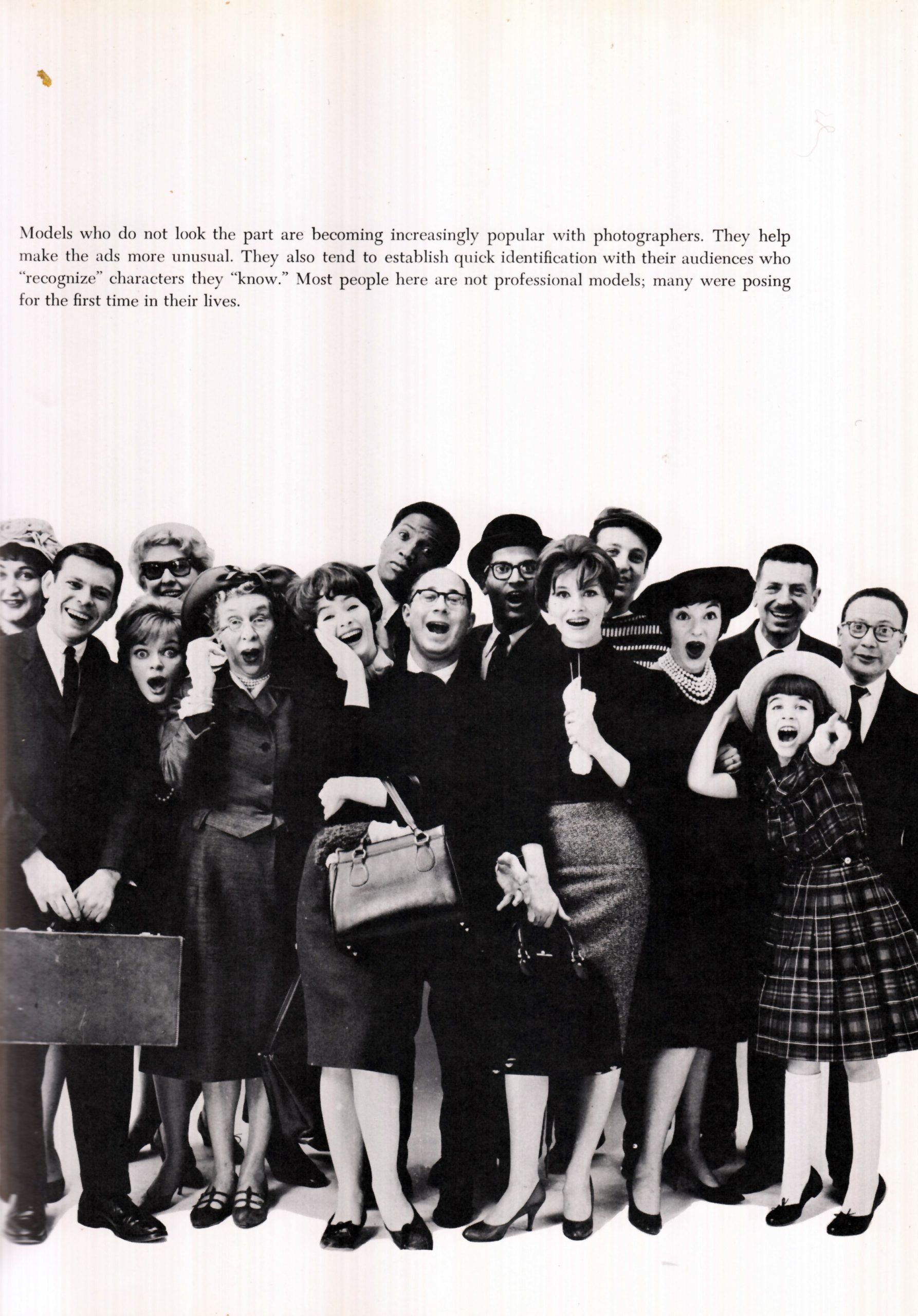

As a child of immigrant parents, I grew up learning English from watching PBS, Sesame Street, specifically. But there were other favorites like 3-2-1 Contact, The Electric Company, and of course, Mr. Roger’s Neighborhood. The logo, with its head looking like a P was seared into my developing brain.

So I’m incredibly saddened to hear that the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, the government-funded entity behind PBS and NPR, will cease operations on September 30, 2025, because of a recent bill passed by the Republican-controlled Congress and signed into law by President Trump.

While PBS and NPR won’t disappear, it will be harder for those networks to stay afloat, now solely dependent on donations.

Lilly Smith, writing for Fast Company:

More than 70% of CPB’s annual federal appropriation goes directly to more than 1,500 local public media stations, according to a web page of its financials. This loss in funding could force local stations, especially in rural areas, to shut down, according to the CPB. Local member stations are independent and locally owned and operated, according to NPR. As a public-private partnership, local PBS stations get about 15% of their revenue from federal funding.

She reached out to Tom Geismar, who redesigned the PBS logo in 1984—the original was by Herb Lubalin and Ernie Smith in 1971. He had this perspective:

There is an ironic tie-in between the government decision to cut off all funding to public television and public radio, and what prompted the redesign of the PBS logo back in the early 1980s.

That was also a difficult time, financially, for the Public Broadcasting Service, and especially the stations in more remote regions of the country. Much of the public equated PBS with the major television networks CBS, NBC and ABC, and presumed that, like those major institutions, PBS was the parent of and significant funder for all the local public television stations throughout the country. But, in fact, the reality is somewhat the opposite. Although PBS local affiliates received a portion of funding from the federal government, it is the individual stations that have the responsibility to do public fund raising, and PBS, in a sense, works for them.

Because of this confusion, the PBS leadership felt that their existing logo (a famous design by by Herb Lubalin) needed to be more than just the classic 3-initials mark, something more evocative of a public-benefit system serving all people. Thus the “everyone” mark was born.

Geismar ends with, “And now, once again, with federal government funding stopped, it is the stations in the less populous regions who will suffer the most.”